In my first post in the ecology track, I talked about the phenomenon of academic fraud, where authors were publishing studies on the grounds of questionable research ethics, be it data manipulation, questionable authorship practices or outright deceptive motives.

Amidst all these scientific fraudsters, one of my major takeaways throughout graduate school was the need to strenuously check the original sources of whatever I was referencing. This means that we can’t safely assume that a study citing an earlier work may necessarily represent said work’s original view. For those uninitiated with the process of writing an academic manuscript, the need to check the veracity of original sources is a huge time sink in any researcher’s life, and it is likely only to get worse as AI-generated content threatens to flood the internet. I myself have made a couple of mistakes over the years of writing manuscripts, citing sources incorrectly because I remembered what they said incorrectly. Such things are bound to happen as one reads hundreds of manuscripts over the course of one’s academic life.

This strenuous need to check the original sources of whatever I read crept into the way I approached the Bible, traditionally revered as the sole, inerrant source of authority among Protestants. In fact, one of the major founding principles of the modern protestant faith (as opposed to Catholicism) is Sola scriptura – essentially translating to “by scripture alone” in Latin. A common accompanying (but not necessarily necessary) belief to this principle is the stance that Scripture is infallible – aka the bible is 100% historically and theologically accurate with absolutely no mistakes whatsoever. Under these conditions, any perspectives contrary to traditional Christian doctrines (e.g. the Trinity, Jesus’s resurrection, biblical inerrancy) can become silenced by “but the bible said…”, inhibiting further discourse.

Biblical inerrancy?

I would expect 99% of all readers of my blog to have never learnt Greek, nevermind read the New Testament’s manuscripts in its native form. Well, neither have I, but thanks to the magic of amazing biblical scholars, historians and BibleHub, the common man now has some access to reading Scriptures through the lens of our ancestors. The most common verse cited in support of biblical inerrancy has to be 2 Tim 3:16.

All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness (2 Tim 3:16 NIV)

All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness (2 Tim 3:16 NKJV*)

*for the die-hard KJV fans

Notice how the first part of the verse translates theopneustos slightly differently (God-breathed vs inspired by God). The NIV translation is more literal (theo = God; pneustos = to breathe into), closely reflecting how God breathed life into Adam’s earthly shell in Genesis. The latter seems to be an interpretation of the former, suggesting that God inspired Scripture directly. Since God gets everything right, all Scripture is equally “right” as well, right? Both interpretations seem plausible, so in true academic fashion I shall defer this question to a true scholar who actually knows their Greek. I personally subscribe to the former view, since it flows nicely into the second half of the verse, reflecting closely what early believers thought of God’s word (Heb 4:12).

For the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart (Heb 4:12).

A more serious and damning issue presents itself in the authorship of the Pastoral epistles (1 and 2 Tim + Titus) themselves. While the text suggests it was Paul, critical scholars have brought up serious issues in believing this was truly the case. Some of these include:

- Even within the rest of the NT, there have been warnings of forgeries lurking around (see 2 Thess 2:2). This itself does not prove that the Pastorals were said forgeries, but that the practice of forgery of Christian writings does exist back then and that readers need to be wary of them.

- The vocabulary in these letters vastly differ from the other genuinely Pauline letters (e.g. 1 and 2 Corinthians). Nearly half of the words in the Pastoral epistles do not exist in the rest of the Pauline corpus and a majority of those unique words are more typical of 2nd century Christian writings.

- The writing style is unusual of Paul, who tends to write very passionately. The style in the Pastorals align closer to the writer of Hebrews, of which few scholars believe is Pauline.

- The writer of 1 Tim silences women in church (see 1 Tim 2:11-15). Would Paul, an apostle who worked alongside Phoebe (a deacon; see Rom 16:1-2), Priscilla and other women (rest of Rom 16) subscribe to such an attitude? Note that while 1 Cor 14:34-36 seems to convey such an attitude, scholars are also convinced that this too is a later addition (a condensed argument can be found here).

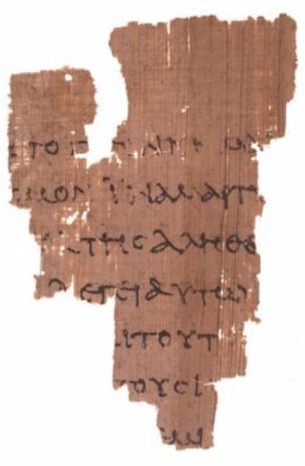

Even if one chooses to reject all of the abovementioned arguments in favor of a Pauline authorship, what kind of Scripture would “Paul” have in mind in 2 Tim 3:16? It would be very odd to believe he himself was writing “Scripture” as defined by modern-day bible readers. Our earliest copies of a full bible corpus (known to us) are the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus; both dated almost 300 years after Paul’s time, so “Paul” would not have the full copy of our New Testament accessible to him. In other words, the writer’s definition of “scripture” would have been vastly different from what we call “scripture” today, and we cannot safely assume that the author would agree that our “scriptures” are all God-breathed/divine-inspired.

Tldr: 2 Tim 3:16 alone poorly supports the view of biblical inerrancy considering that the writer probably was someone impersonating as Paul who possibly did not intend for his point to be about scriptural inerrancy anyways, and the fact that the definition of scripture has evolved over the centuries leading up to our modern-day bibles.

Biblical scholarship has come a long way since Paul’s time. Today, academics are in consensus that only 7 epistles in the NT are almost certainly attributable to Paul (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon). All other books in the NT are classified as either pseudepigraphic (false attribution; e.g. the gospels) or a likely forgery (false authorship). To discover more about how scholars arrived at this consensus, I would suggest checking out the likes of Dr. Bart Ehrman, Dr. Dan McClellan, and a whole range of other non-apologetic sources (I don’t advise looking up sources with an apologetic stance for reasons I will explain in a later post).

How dare you suggest there is fraud in the bible?!

None of the arguments I presented above come from me – these have been the academic consensus for decades. It is only with the prevalence of 1) academics persisting in the most obscure of research areas in the ancient world; 2) the Internet; and 3) scholars who have stepped up to communicate these findings to the general public that have evolved our perspective of mankind’s best-selling book of all time. The modern Christian will likely engage with the bible solely at the devotional and theological level and will never question the veracity of the bible’s claims. This, in my opinion, is a great loss for the church as our theology becomes restricted and inflexible, bending to the whims of biblical inerrancy (which isn’t even that well-supported by scripture itself!).

What does any of these have to do with my introduction about verifying original sources? To the modern reader who will largely consume biblical content secondarily through a translation, a devotion, a pastor or a commentary, consider reading the text in its native form (known to us; more on this next time). For a start, look up on key words in Greek (NT) or Hebrew (OT) and engage with scholars who wrestle with the original manuscripts in those languages. Gulp, don’t sip scripture to holistically consider the worldview of each biblical author. In the same way as a researcher in STEM tries to disprove a hypothesis, we should try as hard as possible to disprove our initial precepts of the bible in order to clarify to ourselves why we believe what we believe.

I forsee several attacks to this post. The first may come from Christians who believe any insinuation of mistakes/contradictions/fraud/forgery in the bible is a challenge against the authority of God and the church itself. Far from it! If you feel that a true believer must subscribe to biblical inerrancy, I would argue you worship the bible and not God. For as long as God has revealed to us through the bibliography of mankind, scripture, holy revelation etc., everyone has seen, is seeing, and will see God slightly differently. That perspective is something we need to develop in ourselves, by ourselves as we wrestle with the text to develop our relationship with the Almighty. Since we are reading events that happened generations ago, academics who revel in the historicity and transmission of biblical events and texts work hard to bring us closer to what our ancestors may have thought about Jesus, God and the divine. Listen to them − they certainly know more than you or I combined (unless you are a scholar in these fields yourself; in that case keep up the good work!)

The second may come from skeptics who see the presence of frauds and forgeries in the bible as a collapse of the integrity of scripture and the idea of God itself. Can one really rationally profess to believe in the Christian God if the scriptures about Him are imperfect, or tampered with? Die-hard atheists may think it is impossible. I disagree (hence this blog!). So does Dr. Bart Ehrman, despite writing entire books on the topic of forgeries in the NT. For the longest time, most people in history would not have had access to a full copy of the bible, yet they found ways to honor what they thought of God through good works. Early Christians certainly did not have a full text known as the “gospels” and the only way they could learn about the good news was through someone telling them. Even today, scholars who lead the field of biblical discourse, including its inconsistencies, forgeries and inaccuracies continue to exercise their faith. People of all ages in all ages have continued pursuing their faith in spite of the imperfections of the biblical stories. Whether that kind of belief is “rational” or not is a matter of philosophy which I am ill-equipped to contribute to. Leave a comment if you have your own take!

There will be some who will never be convinced by those who dare suggest the inauthenticity of scripture, be it the missing ending of Mark 16, the insertion of the story of the adulterous woman in the Gospel of John, the citation of a fake verse in the Gospel of Matthew, etc. Ironically, by enforcing an unchanging theology through insisting on the historical veracity of the text at any cost, they lose out on the theology behind why those inconsistencies are there in the first place. To me, the bible becomes alive when we rightfully recognize it as a compilation containing how generations of people have struggled with perceiving and understanding God and themselves. Occasionally, these authors nail a theological truth; other times they miss the mark through honest mistakes, deceptive means and cognitive biases. Denying these is to deny the humanity of the biblical authors itself which in my opinion, the most unbiblical view of them all.

Leave a comment