What do you imagine the average ecologist does in their day-to-day research? At least within my social circle, ecology is taxonomy and identifying species. Ecology is jotting down in your field notebook, taking observations of what wildlife can be found in ecosystems. Ecology is being harassed by your friends* “wh@t sp3cie5 i5 thi5?”.

*I confess, I am extremely poor at species identification. That is because I specialise in plant function, not taxonomy.

None are quite right.

For a biology-centered specialization, I do a lot of statistics. Like A LOT. Easily thousands of lines of code in R in my entire graduate program. None of this was a particularly big surprise for me since I did pursue a statistics minor prior to my PhD so that I would be extremely comfortable with coding and statistics (plus it improves my job prospects). But I would be lying if I said that just knowing statistics is sufficient to do a PhD in ecology (or in any quantitative field whatsoever). Statistics isn’t a single tool – it is an entire toolbox scientists utilize daily to analyze/torture their data. The hard part is knowing when to use what, and why. And that brings me to the topic of this post.

Are dark-skinned football players more likely to get red cards?

<Make a guess before you read on!>

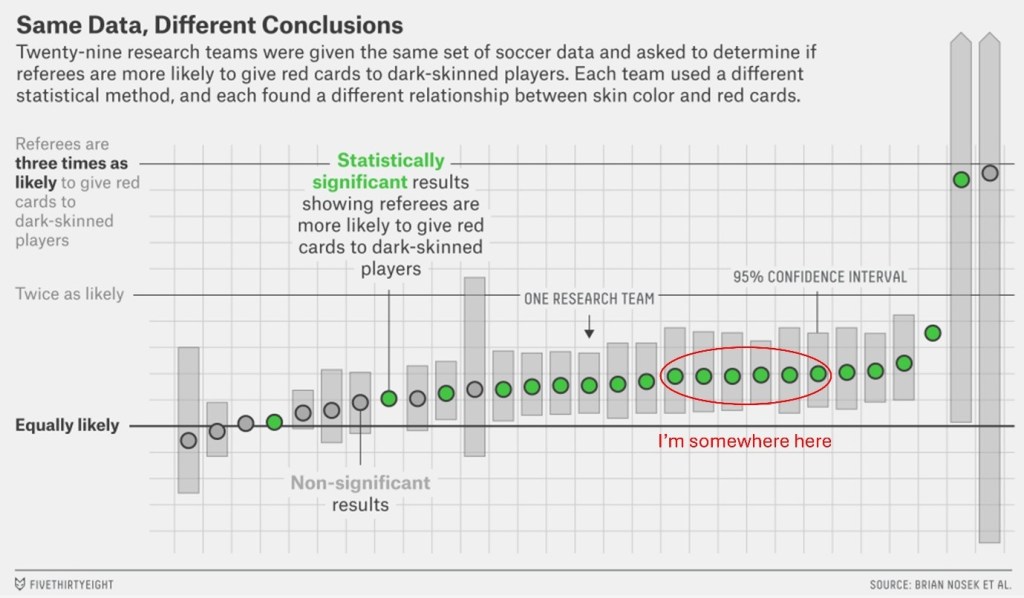

This is the question Nosek and colleagues posed to 29 teams of researchers from a diverse array of research fields. What these authors did were to release a publicly-available dataset of thousands of football players’ records which included a rich array of possible cofounders/covariates such as the height, weight and country of origin of each player. Naturally, the dataset also came with a scale of measuring how “dark-skinned” each player is (on an ordinal scale from 0 to 1 in increments of 0.25) and the number of red cards they were awarded in each player-referee interaction.

Give some thought on how you would address this question. Do you include all the variables given as covariates? If not, which ones (and why)? How would you account for differences in the number of games each player plays (and when/where they were played)? What kind of model would you use?

For those outside the academic space, these are questions that scientists deal with on a daily basis. In school, the curriculum is structured such that you are learning science “facts” as opposed to learning the scientific process. They are not the same, and that difference is what separates a science trivia whizz from a professional research scientist.

So, what is the “correct” way to deal with the question and the dataset? Truth is, there isn’t one (at least there isn’t one written in some stone tablets like the ten commandments).

Nosek and his team were not concerned with arriving at a definitive conclusion that dark-skinned football players are more discriminated against; it was a test to see how different approaches to data manipulation and analysis can yield a diversity of conclusions. On one end, there were researchers who took the simplest approach using Spearman’s correlation or multiple linear regression. On the other end, you got teams bringing out the heavy artillery with complex methods such as…<checks paper>…”Dirichlet Process Bayesian clustering”??? I have no idea what that is.

Back to the study. Here is my approach to this problem. Let me know your thoughts and what you’ve found!

My proposed answer

I don’t play soccer nor I am well-versed with implicit/explicit biases in psychology. Nevertheless, these are my first impressions of the data:

- Clearly, the observations of red cards and player-referee interactions are not going to be independent (e.g. the same player interacts with multiple referees across the games played). Some form of hierarchical modelling is required to account for this. My personal stance is that any methodology that did not account for non-independence among observations should be cast out automatically.

- Most of the time players don’t get awarded red cards (~99% of all observations). Hence, I am initially inclined to use some form of zero-inflated model, but the data needs to be checked for zero-inflation and overdispersion (I did not find any to be true).

- Since each player-referee interaction has multiple games and up to two red cards awarded across those games, this seems like a binomial problem (x successes across N games). Maybe a mixed effects model with a binomial distribution is called for?

- What other factors could impact a referee’s decision to give a red card? These could include the physical characteristics of a player, which club the player comes from (maybe the referee hates Liverpool for some reason), the player’s position (strikers may be more aggressive) and the implicit/explicit bias scores of the referee. These should be included alongside the fixed effect (skin colour rating of the player).

Putting all of these together, I landed on a mixed effects model with skin color rating, height, weight, mean implicit bias score and mean explicit bias score as fixed factors and player, player’s club, position and referee ID as random effects. I assumed a binomial distribution for the response variable (red cards awarded) with a logit link. In the original paper, my model would have probably resembled team 25 most closely and I would have reported that darker skin color is positively associated with the odds of getting a red card (Odds ratio = 1.36; P = 0.005).

How did I score?

Objectivity in science and religion

I don’t expect anyone but the nerdiest of people in the world (aka the Permanently Head-Damaged) to come across my post and actually understand what I did above, or why I would even trouble myself to do the analysis myself.

I did it to illustrate a point for readers outside the academic space. Dozens, if not hundreds of decisions go into every research project. These include seemingly trivial things when designing an experiment (e.g. arranging flower pots in a greenhouse) to decisions made in data analysis (should I standardize? should I log-transform? what model should I use?). Unlike science in school, there is no right answer – it doesn’t exist at the back page of a textbook. It is for us to decide using reason and logic. That is why George Box quoted “All models are wrong. Some are useful.”. The point of analyzing empirical data isn’t to arrive at some truth inscribed in stone, it is to provide a useful approximation of reality to advance society’s understanding and condition. Not everyone gets it right all the time, either through lack of experience, disagreements in methodology or outright fraud.

All models are wrong. Some are useful. – George Box, 1976

At this point, is there even any measure of objectivity in science? This is a sticking point for fundamentalists who reject science because “scientific opinions change”. My personal view is that science itself can never be fully objective because every scientist is a product of his/her experiences and biases and these are things that will influence the way we approach any topic. Nonetheless, it is the best we got when it comes to making objective deductions about the universe.

In the same way, even for the devout, I find little meaning in claims such as “God’s word is unchanging” or “God’s truth is objective”. So what? We are not God. What we have on earth is Scripture about and of Him and reading and interpreting Scripture necessitates passing what we read through a human’s writing and a human’s lenses. This opens up to all sorts of biases and limitations, just like any other field. Relying on your faith’s sacred texts for objective truths is as objective as relying on science alone to do the same. You can’t escape subjectivity.

Like science, religion will need to recognize that a change in opinions is not a bad thing, letting go of dogmas is ok, and there is nothing sinful or weak-willed about changing your stance on homosexuality, or abortion, or capital punishment. Instead, it shows a willingness to update one’s perspective based on the most current knowledge and arguments known to mankind. Holding on to any of our precepts or principles too tightly is not a sign of strong faith; it is a sign of insecurity and stubbornness. In contrast, we practice humility when we rightfully recognize that no single source has all the answers to the questions in society (not the bible, nor any scientist), and we need to be open to change when new information or perspectives are introduced to us.

That is already a feature in science. I hope it becomes a more widespread feature in my faith too.

Leave a comment