“Climate change is a hoax! Scientists’ climate models are wrong!”

If you have heard this, I guess you are no stranger to the many claims climate sceptics use to undermine the urgency of ongoing climate change and the researchers involved in studying, modelling and predicting it. Since the late 1900s, scientists have started ringing the alarm bells to alert the possibility of a warming planet and a destabilizing climate. Some have acknowledged and heard the call, while others have chosen to call these bells “bullshit”.

So, who is right?

This was a question that Hausfather and his team sought to answer in a research article published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. What these authors did was compare predicted global mean surface temperature (GMST) changes up till 2017 from climate models built between 1970-2007 to see if these models produced good projections on GMSTs that did not deviate far from reality. While many of these models were far less sophisticated than models used today, a majority of them still produced predictions consistent with observations. For a more detailed treatment on the accuracy of climate models, I propose checking out Dr. Simon Clark’s video here.

To me, seeing news like this is one of the most validating feelings one could get as a scientist in a field plagued by so many polarizing views. Essentially, seeing models correctly predicting the future almost feels like having a superpower of precognition. This highlights what science can do if left to flourish properly – it gives us a unique power to understand, model and predict the world. It is truly unfortunate that right now, those who wield such power are seen as a financial burden at best to a threat to society at worst.

I am no expert on climate science nor any form of modelling or forecasting. What I did wonder instead was whether there were similar tales of precognition in the world of ecology? Are there models or studies out there that predicted something about an ecosystem, a species or a community back then? Were their predictions validated?

Ecological theories

There has been an abundance of ecological theories put out over the past few decades; many of them have since been cemented as staples for ecologists today. Some of the ones I can recall off the top of my head include the theory of island biogeography, successional theory, and trophic cascades. I think it would be a fair statement to say that these theories absolutely hold true in some scenarios. Yet, I always wondered if we ever surveyed a new uncolonized island, will we really find the number of species stabilizing towards a number that we can predict? Did someone from long ago observe a newly deforested site, predicted which species will colonize at which times, and was actually validated for his/her predictions? Has someone actually made a prediction of a trophic cascade in an ecosystem that saw an apex predator being removed, and was actually shown to be right?

If any reader comes across this post and knows of such examples, I would love to hear from you! But right now, I struggle to think of a single example of a validated ecological prediction at the same scale as climate models. I don’t mean a trivial prediction like seeing an empty field and predicting that it will be colonized by grass next year. What I mean by a proper long-term ecological prediction includes:

- A theory/model makes a falsifiable prediction on the state of an ecosystem in a constrained timeframe, preferably 10 years or more. This prediction should not be changed once made.

- The ecosystem is then monitored regularly up till said timeframe.

- Someone did a write-up comparing empirical observations vs said prediction.

Are ecologists just bad at their jobs?

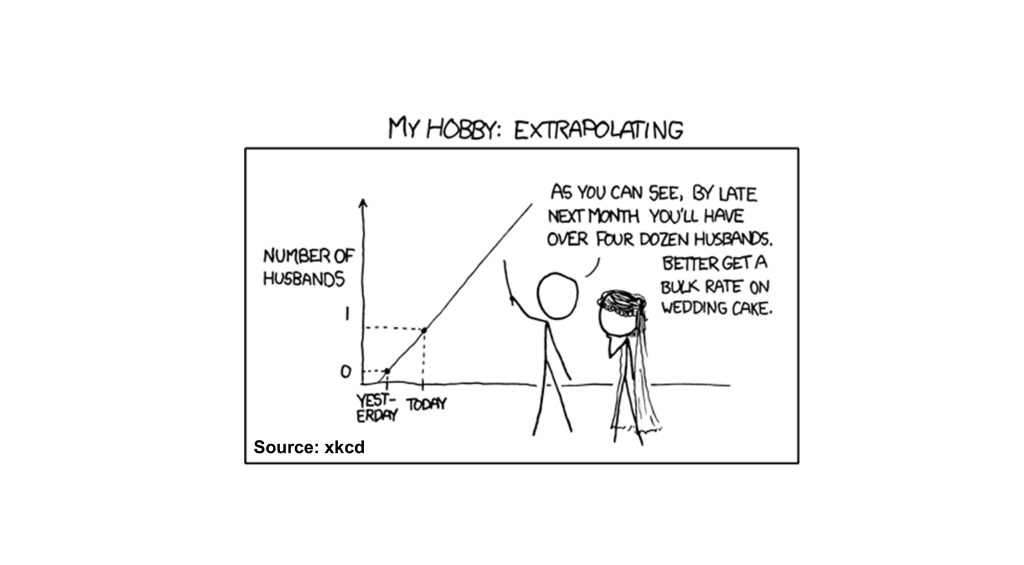

A study by Low-Decarie and colleagues found that while ecologists are employing more complex models in publications, the R2 values reported in these publications have been on a steady decline. For the statistically illiterate, it means that statistical models employed by ecologists in recent years are declining in explanatory or predictive power. This phenomenon is even more damning if we consider that studies with weak R2 values and insignificant P-values typically don’t get published. Heck, even in my own research, I encountered an R2 of 0.01 before WITH a significant p-value! Is a significant result even worth writing home about if the model only explains 1% of total variation? I leave it to the reader to decide.

What does all this mean for the field of ecology? The dim view would be to assume we are half-baked at our jobs if we cannot even produce a single well-informed prediction of the systems we study. The optimistic view would be to recognize that nature is inherently messy and often does not play by our rules and presuppositions, so it is nothing surprising if we get it wrong more often than not. But at some point, if the most informed among us can’t even get anything in ecology right, who can?

My personal motivation as an ecologist is to be able to produce scientific results that reflect accurately the state of ecosystems and can further be applied to better predict or manage ecosystems we care about. I don’t revel in theory; I want to be validated in my predictions of nature based on what has been known or discovered. I want to experience that ability of precognition, even if it is just for a little bit. And I think any ecologist worth their salt should be doing work that actively strives towards this goal. If not, our theories will remain merely as theories – useful to us, useless for the world.

Leave a comment