Two Christians read the same bible. One goes on to protest against welfare benefits for the poor; another supports it.

Two Christians read the same bible. One calls for increased love and acceptance for the LGBTQ community regardless of their sexual orientation; another supports conversion therapy to change who they are.

Two Christians read the same bible. One chooses to raise support for proper environmental stewardship. Another does nothing, even desiring the hastening of environmental destruction while asserting one’s dominion over Creation.

Two Christians read the same bible. One supports the aggressor in committing genocide to ensure victory for God’s chosen people. Another condemns the aggressor and stands up for the victims via protests and charity.

For a religion that promotes a unified truth, Christians all around the world arrive at wildly different answers in the face of life’s issues. At least, among Protestants, we read the same 66 books of the Bible. We subscribe to the same God. We are tutored by the same Holy Spirit and the teachings of our Lord and Savior. Yet, we see Christians scattered all along the moral spectrum, ranging from evangelicals who engage in sexual abuse, to believers who sacrificed themselves to stand up for others. Is it a problem with our beliefs being ill-defined? Or is it a problem of us not having enough faith? Or could it be that people act in ways that don’t always align with what they profess to believe in?

The relationship between faith and good works

For we hold that a person is justified by faith apart from works prescribed by the law…For if Abraham was justified by works, he has something to boast about, but not before God. For what does the scripture say? “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.” Now to one who works, wages are not reckoned as a gift but as something due. But to one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, such faith is reckoned as righteousness. (Romans 3:28; Romans 4:2-5 NRSVUE)

Do you want to be shown, you senseless person, that faith apart from works is worthless? Was not our ancestor Abraham justified by works when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? You see that faith was active along with his works, and by works faith was brought to completion. Thus the scripture was fulfilled that says, “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” and he was called the friend of God. You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. (James 2:20-24 NRSVUE)

These two verses are commonly cited to capture the need for faith and works in the lives of believers. Protestants typically reconcile the two sets of verses above by espousing that justification is achieved solely through faith, and through this proper faith that we are automatically driven to produce good works. In the words of John Calvin: “We are saved by faith alone, but the faith that saves is never alone”.

Aside from the point that both authors were not even on the same page in terms of “faith” and “works”, this perspective has become a staple for most protestant believers today. The corollary to that perspective is if a person does not yield good works, he/she never had genuine faith to begin with. In modern times, this corollary has been invoked to criticize believers who later backslided, left the faith altogether, or engaged in behaviors contrary to the faith, such as the lack of good works.

To me, such a theology feels a lot like the “No True Scotsman” fallacy where we arbitrarily redefine who has genuine faith or not based on the works in their lives. Moreover, such a theology presupposes that “faith” always yield “good works” (John 15:5 is often cited for this). Notice how the words “faith” and “good works” appear in quotations – both terms are extremely murky and difficult to define cleanly, yet these form the foundational beliefs of millions of believers across the world today.

What I want to explore in this post is the preposition that one’s sincere belief (in God) always drives an individual towards good works. Obviously, empirically testing the link between the two is extremely difficult given the diversity in Christians’ beliefs and their views on what encompasses “faith” and “good works”. Nonetheless, even these ambiguities together do not seem to sufficiently account for the diversity of behaviors produced by believers worldwide.

Take for example the following thought experiments:

Scenario 1: Giving to the poor

If anything, this is one of the commands explicitly expressed by Jesus (Matt 25:31-46; parable of the sheep and goats) and the OT (e.g. Deut 15:11) on the need to give to the poor. Not the spiritually poor (as how Luke 6:20 is sometimes interpreted), the literal poor. I don’t think any sane believer will deny this as a core tenet of the faith to help others in poverty.

Yet, do we all give to the poor? I donate to charities from time to time, but not always. I’m sure many believers outright do not. What gives?

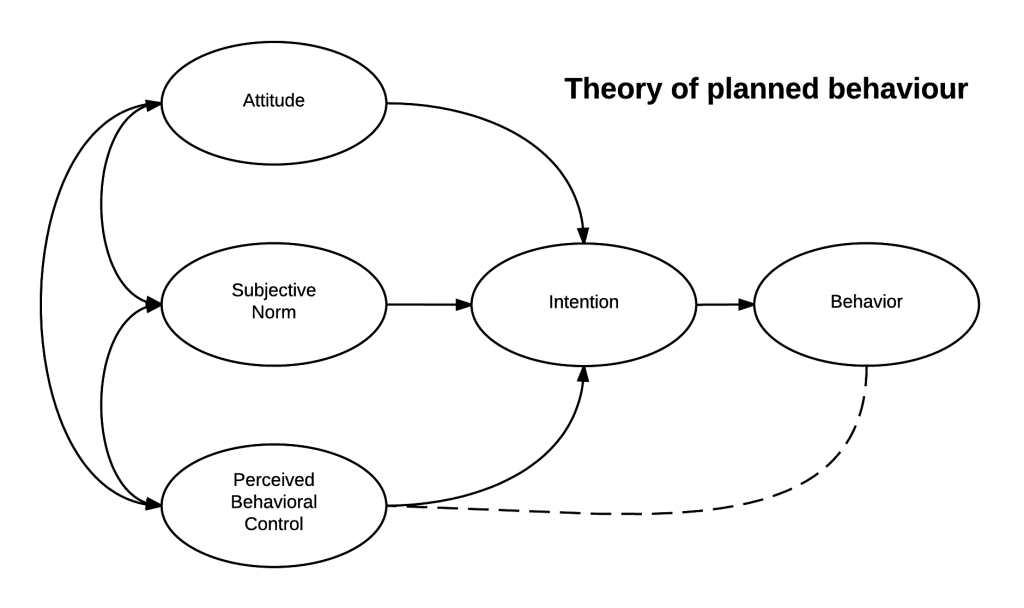

This is when a little human psychology comes in. The theory of planned behavior proposes three factors that drive human behavior:

- Attitude towards the behavior (should the action be done?)

- Subjective norms (do others around me feel the action should be done?)

- Perceived control (thinking whether the action can be done due to internal or external factors)

All believers should immediately answer “yes” to the first, and probably the second as well. But when we come to perceived control, this is when human tendencies fluctuate wildly. I shouldn’t give because it won’t solve the problem of poverty. I shouldn’t give because it encourages laziness among the poor (even though this is largely untrue). I shouldn’t give because I don’t have enough to give (is it ever enough?). I don’t want to give because I am afraid of getting scammed.

This isn’t meant to be construed as a criticism of the morality of believers. Rather, it goes to show how identical beliefs do not always translate into the action demanded out of us from Scripture, however abundantly clear it may be.

Scenario 2: Evangelism and missionary work

Sharing the gospel may come naturally for some but not for many (myself included). The Great Commission (Matt 28:16-20) is another central tenet in protestant churches and most believers believe in some capacity that we are all called to spread the gospel to the ends of the world.

Applying the same theory as before, most, if not all believers should easily agree that we should be bringing the gospel to those who have yet to know him. However, do you feel that others will feel the same way (especially people from other religions)? In cosmopolitan cities, you might feel pressured to keep your beliefs to yourself out of respect for the beliefs of others (negative subjective norms). You may not be fully convinced of the efficacy of evangelism or missions and refuse to participate in those efforts (lack of perceived control). And this doesn’t even account for the differing views in how evangelism should be done among believers (door-to-door, service-oriented, local or overseas missions etc.).

Again, this isn’t to shame any particular believer if they are not involved in an evangelical ministry. Just because we have a common belief in the words of Scripture doesn’t mean we end up taking the same action.

These two scenarios are just some of the tamer decisions that the average believer might face in their daily lives. Yet, the same principle applies to many of the societal issues outlined in the introduction of this post where the God-ordained course of action remains murky. The late Pope Francis didn’t approve fully of homosexual relationships (he remained steadfast that homosexual acts are sinful), yet he called for the decriminalization of LGBTQs. Yet, we are starting to see the exact opposite in parts of the US.

Does faith always drive good works?

In my humble opinion, based on the observations of my life and the behaviors of Christians elsewhere, no. Faith is not a guarantee of good works. Faith is a complex thing, and it competes and synchronizes with human motives and perception before it translates into behavior.

One might argue the lack of good works in the scenarios above might be a result of the lack of intensity in one’s faith. I don’t think that reasoning checks out. Considering just how much of the synoptic gospels contain teachings that emphasize good works without even the mention of faith, I find it hard to rationalize the need for such teachings if doing good works came so naturally after having faith. In my eyes, such a theology severely downplays so much of the OT and Jesus’s own teachings to care for the poor and stand up for the marginalized – things we clearly affirm and believe in yet find it so hard to do on a regular basis. Furthermore, there exists many pious individuals who end up committing great sins. Just ask any of these disgraced pastors if the works they did were good.

Where does good works stand in our faith then? Perhaps in a future post, I might write something about the history of sola fide (faith alone) and how the early church wrestled with the problem of works versus faith. For now, suffice to say if Christians really desire to remain as salt and light to the world, proclaiming great faith alone won’t cut it. The world judges us by our deeds, and Jesus will cast out the ones that don’t produce good fruit. We need to find ways to get that faith realized in loving deeds, either by helping believers remove the obstacles of perceived lack of control and/or negative subjective norms or by reinforcing the need for believers to assert control of their behavior and actively choose to live in a Christ-like manner for Christ Himself.

Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; therefore every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire. (Matt 3:10 NRSVUE)

Leave a comment