In a previous post, I expressed my viewpoints on prioritizing some species over others in conservation, and the dilemma conservationists face when it comes to allocating resources for species conservation.

Amidst the doom-and-gloom in conservation, the silver lining is that more groups are paying heed to the alarming rate of biodiversity decline in our world and are taking active steps to mitigate this decline. Assessing this decline, however, requires one to have a baseline to compare to, and to establish an “ideal state” of biodiversity and ecosystem health that conservation efforts should strive towards.

This baseline is a hot topic in ecology today, especially when we start to bring in climate change and anthropogenic influences on biodiversity in modern times. Take for example a tropical forest that has documented to be undergoing degradation, gradually losing some of its flora and fauna in the process. How much total biodiversity is lost depends on how far back you go in time and what baseline you pick as your starting point for comparison. For restoration and conservation practitioners, should they strive to restore biodiversity to the state it was 20 years ago? Why not 40? Why not 100? Heck, why not 0 (accept the status quo that is the new norm)?

Challenges in choosing baselines

Choosing a baseline in conservation isn’t a trivial task. Firstly, our biodiversity records are often not as detailed as we would like them to be, making it difficult to establish what species were present back then, and how they looked like. This is especially true in remote, species-rich environments such as tropical forests – even till today, we barely know what’s out there.

Secondly, ever since the Industrial Revolution occurred, humanity’s impact on native ecosystems have accelerated through the moon. This does not simply encompass modern threats such as climate change. It encompasses past land-use change, introduction of ornamental species going rogue, natural hazards such as wildfires etc. When we look back into the past, these historical events blur the line between what was pristine and what we have today. In fact, so prevalent is this phenomenon in our psychology today that experts has given it a name “shifting baselines syndromes”.

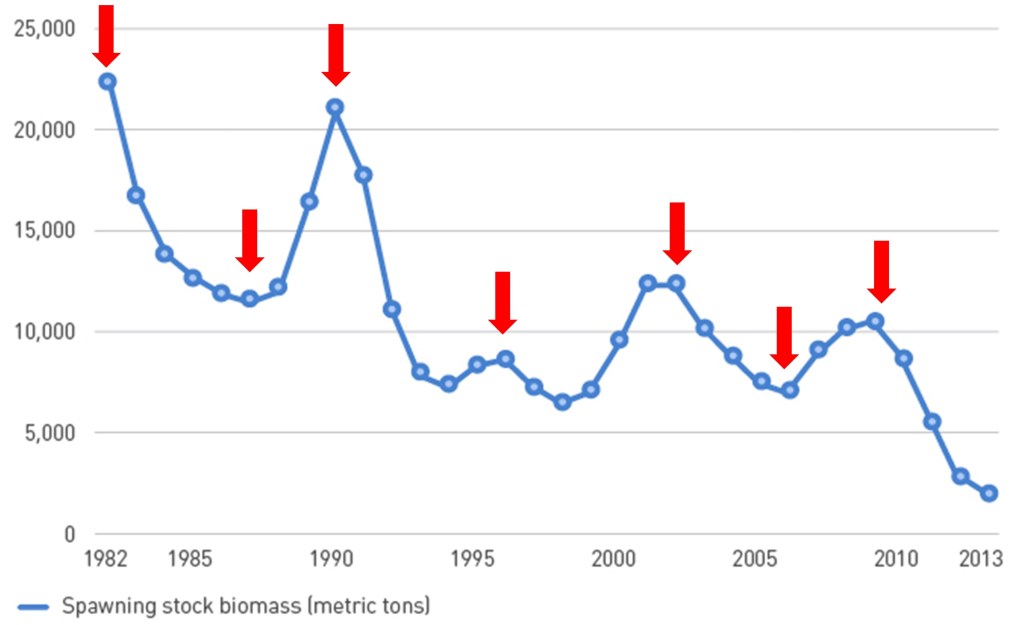

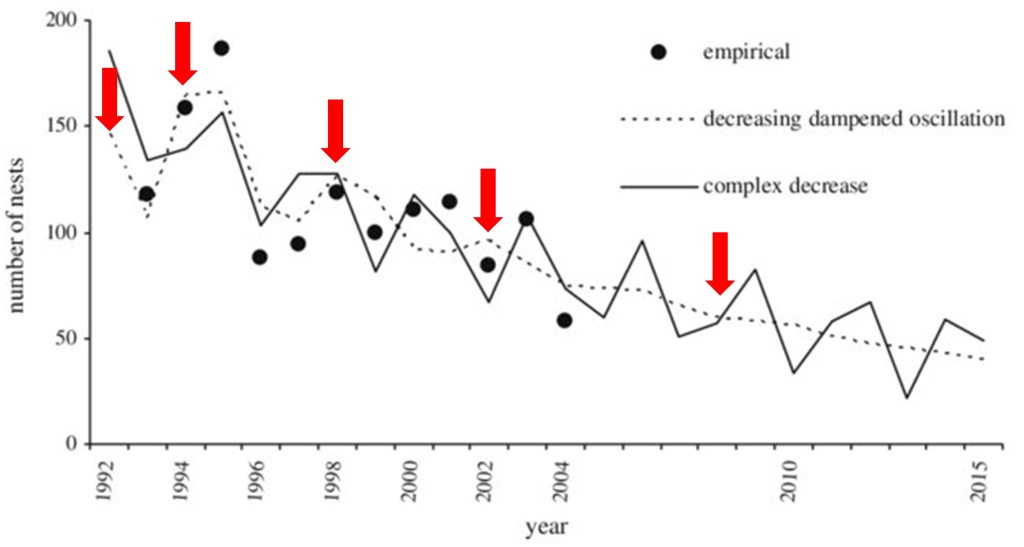

Baselines may be easy to establish if it is known that the loss in biodiversity in an ecosystem is a result of a one-off catastrophic event, such as a wildfire or a logging event. However, many ecosystems around the world still face a decline in local biodiversity, even in the absence of such events. For example, the persistence of fishing and overexploitation of marine resources in the past half a century has resulted in a decline in the populations of Atlantic Cod (Fig. 1), whereas human activity likely caused a decline in the loggerhead turtle populations at Fethiye, Turkey (Fig. 2). If you were tasked to initiate a conservation effort in those areas to restore the populations of these species, which part of the graphs below would you pick as your baseline/target?

Fig. 1: Time series of reproductive-age Atlantic cod in Gulf of Maine. Graph from Carbon Brief, with original data from Pershing et al. (2015). Which of the red arrows would you use as a baseline for cod populations for conservation?

Fig. 2: Time series of loggerhead turtles nests found at Fethiye Beach, Turkey. Graph from Ilgaz et al. (2007). Which of the red arrows would you use as a baseline for turtle populations for conservation?

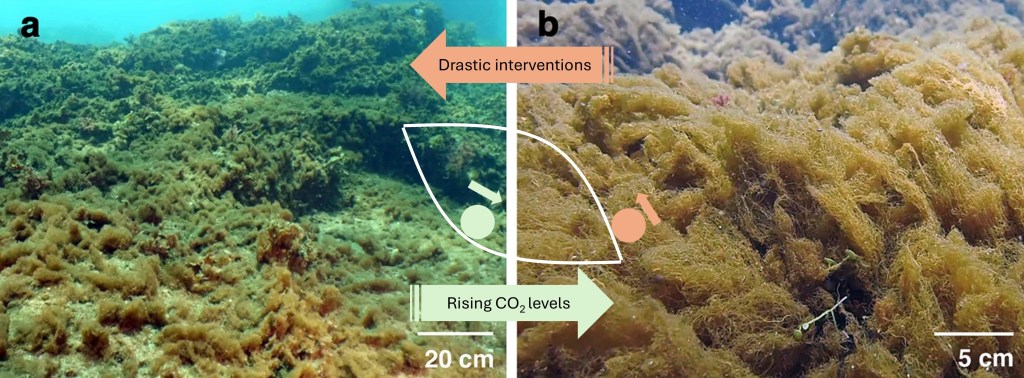

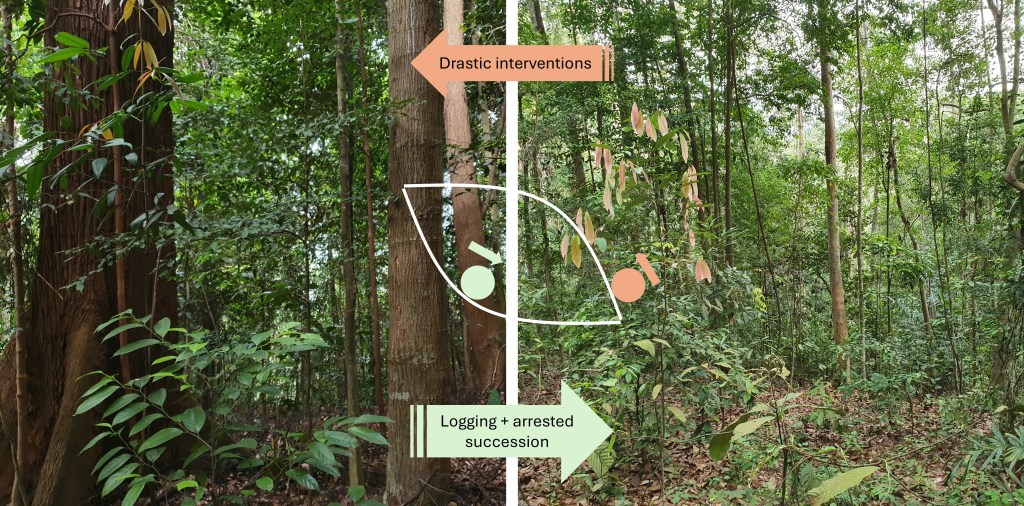

Finally, even with our best efforts, we are unlikely to see the successful restoration of many ecosystems and their wildlife no matter how hard we try. In ecology, this is known as hysteresis, where an ecosystem declines to the point where it rolls down a slippery slope into a new, alternative stable state that cannot be easily reversed barring drastic measures. Anyone who has taken an introductory ecology course would be familiar with the many classic examples of hysteresis – degraded coral reefs, drained peatlands, arrested succession of logged forests etc. In these ecosystems, even though the baseline appears obvious (the pristine states), getting there may be near impossible or unrealistic with the current amount of resources and technology available to us.

Fig. 3: Regime shifts in coral reefs from coral-dominated to turf algae-dominated off the coast of Shikine Island, Japan. Rising CO2 levels drives ocean acidification, which promotes and maintains the explosion of turf algae populations that cannot be easily reversed. Photos and information from Harvey et al. (2021).

Fig. 4: Past logging events and arrested forest succession of the primary forest (left) has led to a new stable regime in the secondary forest (right) with distinct floral communities.

Aren’t baselines an arbitrary problem?

At the surface, choosing baselines seems to be a pedantic exercise for pedantic ecologists to squabble about. Yet, the problem is not as arbitrary as one might think. As mentioned above, the baselines issue is so prevalent to the point where conservationists have dubbed it “shifting baseline syndrome”. Essentially, the more we allow this biodiversity loss to persist due to anthropogenic activity, the more we normalize biodiversity loss and become less willing to take action against it. We already see that right now – young people are gradually normalized to local extinctions and changes in their local ecosystems compared to our elders. If left to fester, the world will become increasingly apathetic and ignorant towards the loss of wildlife, and the next generation will grow up with a warped perception of what healthy ecosystems ought to look like.

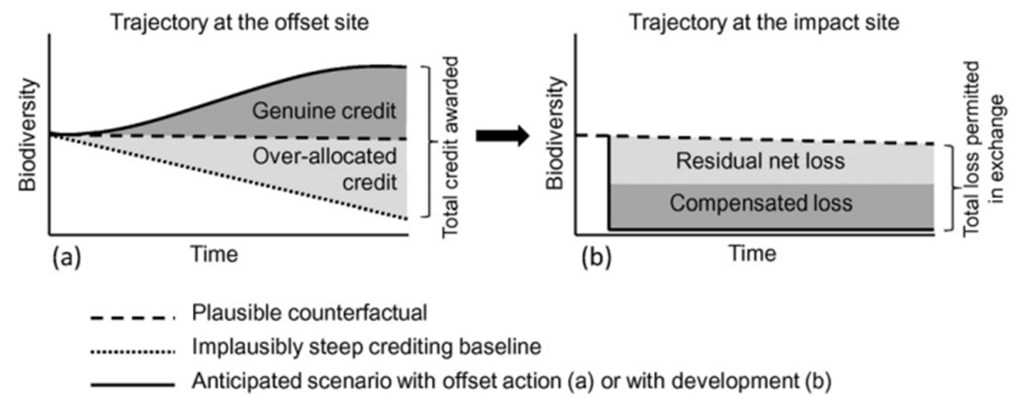

I foresee a second issue that could present major problems in the upcoming decades. For better or worse, more companies are hopping on the bandwagon of biodiversity credits. Like carbon credits, biodiversity credits serve as a currency companies can generate by financing and supporting efforts to conserve and restore ecosystems and their inhabitants. Thus, if done properly, these credits should generate a net positive impact on biodiversity and conservation. Yet, what baseline (the default scenario) are we comparing this “positive impact” to? In a future where the perception of biodiversity loss is increasingly normalized everywhere, scheming companies may arbitrarily assume an implausibly steep decline in biodiversity as their baseline to claim more credits than warranted, giving others a license to continue degrading ecosystems elsewhere. To add salt to the wound, unscrupulous companies could take advantage of the perceived normality of biodiversity decline in ecosystems to select a baseline that minimizes their operations’ impact to wildlife to preserve their image. Large institutions and governments with a pessimistic outlook may also set increasingly lower targets for mitigating biodiversity loss, which can then cascade into weaker enforcement and regulations concerning companies’ roles in environmental degradation.

Fig. 5: Assuming implausible scenarios of biodiversity loss may lead to overcrediting of biodiversity credits. Figure from Maron et al. (2015).

In other words, baselines absolutely matter for successful environmental law, policy and markets.

Countering shifting baselines syndrome

Is biodiversity doomed then? Are we destined for a barren world?

Yes, if we let this biodiversity decline be normalized in our minds. But we don’t have to.

More people nowadays, especially in urban centers, are growing increasingly apathetic, or even fearful of nature. This could be due to the demands of modern life which takes away space to connect with nature, or a lack of access to diverse, species-rich, natural ecosystems where one can observe biodiversity in its pristine glory. Regardless of the reason, people don’t have to accept this biodiversity loss as normal. Society doesn’t have to accept this biodiversity loss as normal.

Here is what I propose to be the best weapon against shifting baseline syndrome: education and policy. The world needs more ecologists to study what’s out there in the natural world. We need to educate a new generation towards nature-literacy, eager to study communities of the past and species of the present to aspire towards what our biodiversity could look like in the future. In the same way that historians study the past to give us insights into our current beliefs and structures, paleoecologists and taxonomists document past communities to give us insights on how the world’s biodiversity could have looked like today (had we exercised better environmental stewardship). Finally, we need political and business leaders who actively consult these ecological record-keepers to set and maintain rigorous benchmarks on biodiversity that won’t shift in the face of apathy and political forces.

Even with all these in place, there is still no guarantee that we will be able to save most of biodiversity. Like the carbon market, companies have found numerous ways to skirt legislation for carbon credits and offsets through creative accounting (or blatant misuse); I wouldn’t be surprised if the biodiversity credits market undergoes a similar process.

But at least it’s a start on the right track.

Leave a comment