Over a decade ago, Elon Musk said in his interview with Khan Academy that “most PhD papers are pretty useless” (see 9:30 in this video). This caught on in the social media since and many media outlets since have boldly (often without sufficient justification) claimed the decline in usefulness in academic research.

In a similar fashion soon after, Derek Bok wrote in his book “Higher Education in America” that “Some 98% of articles in the arts and humanities and 75% in the social sciences are never cited. Things are not much better in the hard sciences-there, 25% of articles are never cited and the average number of cites even of those is one or two.” While I don’t know if he made a value judgement about academia following this statement (I don’t have access to an original), this quote too made it into mainstream media and became a label of the futility of academia research.

While the statistic itself seems dubious and probably untrue for most fields, this made me wonder how useful is ecological research? Science has received a huge bout of criticism in the past few years ranging from the replication crisis, perverse motivations and sketchy academic practices, so it seems sensible to ask whether ecology should be subject to the same criticisms as the other hard sciences.

Obviously, I am still junior to the field of ecology itself having just completed my PhD, so I am not nearly qualified to make a value judgement on behalf on the entire field of ecology. However, with new analytical tools embedded in databases in WebOfScience and Scopus, it is now possible to get up-to-date information on bibliometric information of publications. Using those tools, can we say whether ecological research is useless (or otherwise)?

Here’s what I found.

How often are papers in ecology cited?

I conducted a search on the WebOfScience Core Collection series using only 1 keyword in the search query “ecology”. I restricted the search enquiry to capture only articles/review articles in English only. This returned some 600,000 entries and a ton of irrelevant entries, so I used WebOfScience’s filter functions to restrict the categories* and research areas** of the entries to the fields shown below:

*Categories: Ecology, Marine Freshwater Biology, Environmental Sciences, Evolutionary Biology, Zoology, Plant Sciences, Biodiversity Conservation, Forestry, Microbiology, Oceanography, Environmental Studies, Biology, Behavioral Sciences, Genetic Heredity, Entomology, Geosciences Multidisciplinary, Geography Physical, Fisheries, Soil Sciences, Geography, Ornithology, Agronomy, Parasitology, Mycology, Agriculture Multidisciplinary and Physiology.

**Research areas: Environmental Sciences Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, Marine Freshwater Biology, Zoology, Biodiversity Conservation, Plant Sciences, Forestry, Microbiology, Agriculture, Oceanography, Entomology, Physical Geography, Behavioral Sciences, Genetic Heredity, Fisheries, Parasitology and Mycology.

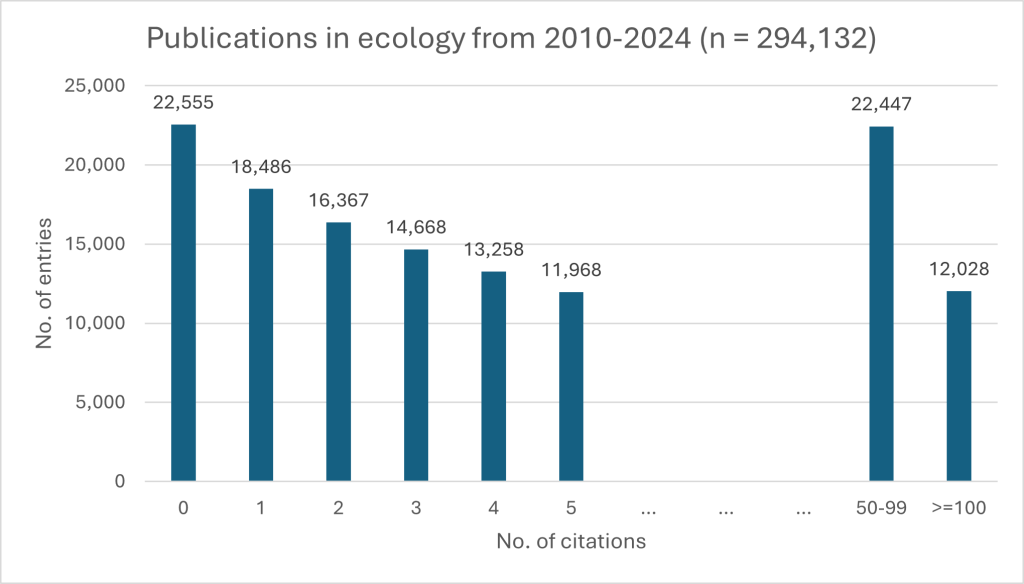

These are the fields which I feel are probably what most people may consider falling under “ecology”. Given the sheer number of entries, I am unable to download all of them into a nice spreadsheet to sieve out irrelevant entries barring the use of scripting tools or a program to download every thousand entries into separate spreadsheets. Nonetheless, I think this gives a good sense of the breadth of work that ecologists have been working on for the past two decades or so. This yielded 294,132 publication entries from 2010 to 2024.

Among these published papers, here is what I found:

The top-cited publication goes to this paper by Excoffier & Lischer (2010), sitting at 13,536 citations. The top-cited publication that isn’t about a method or software package sits at #4 and goes to this paper by Allen et al. (2010). I was surprised to see that the top paper was not published in one of the big three journals in Science – I guess it goes to show that there can be gems even in lower-ranked journals. About 33% of all publications captured were cited 5 times or less, and 7.6% of all publications never received a single citation.

I was pleasantly surprised to find that most papers (92%) received at least one citation, even if citation count remains a crude way of measuring impact (I was initially expecting something damning, like 50%). I’m sure the percentage is likely to go up even higher if one looks at other metrics of impact, such as no. of times read or downloaded.

But what if there has been an influx in low-quality, uncitable junk in recent years? Could bibliometric analysis shed light on such trends? Here is what I found when I restricted my search to publications from 2020-2024 only, yielding 119,547 entries.

The top-cited publication that went out in the past 5 years goes to this paper by Zheng et al. (2020) looking at the taxonomy of Lactobacillus, sitting at just over 2000 citations. Now, over 55% of all publications were cited 5 times or less, with about 1 in 7 papers left on the shelf. The greater number of zero-citation papers isn’t particularly unusual given that it takes time for papers to be cited (not to mention that ecologists publish slower than most other fields given the nature of collecting ecological data), but I don’t know if that warrants nearly double the rate of zero-citation papers (14.4%) compared to the above pool of 2010-2024 papers.

Closing thoughts

These analyses are by no means a formal investigation into the state of publishing in ecology and I don’t have the luxury of time to do one at that scale (unless someone wishes to hire me as a postdoc to do so). There could be duplicate entries, irrelevant studies that sneak into the results and authors self-citing their own past work which could jack up the citation count of some of these studies. It is also hard to tell the extent at which predatory journals and sketchy studies influenced these findings.

Nevertheless, based solely on the above trends, here are some of my closing thoughts:

- The statistic at the start of this post by Derek Bok isn’t a representative picture of ecology publications. Most papers are still cited! (phew)

- What does Elon Musk mean by “most PhD papers are pretty useless”? If we are going by citation count alone, the numbers don’t back up his point (at least within the field of ecology). If he is talking about impact of each paper, I don’t know where he is getting his data from (my guess is he’s just fluffin’).

- Zero-citation ≠ zero-impact. I have one review paper that I wrote up early in my PhD during pandemic times. While I don’t have any expectations of that paper being cited anytime soon, I did receive informal requests through email asking for the data that I compiled in support of that paper. Academics communicate with each other to ask for data or to discuss new perspectives all the time, and this is something citation counts alone cannot quantify or capture.

- I suspect the inverse is true as well: many citations ≠ high impact. For instance, reviews tend to gather more citations than empirical papers (they are easier to read, and these give new researchers a broad glimpse into the state of consensus in the field). But at least in my line of research and stage of maturity in academia, I am no longer excited by yet another review/framework paper, or even a meta-analysis – give me more new data please!

- Do publications in ecology translate into changes in the way we manage, predict or do conservation and/or ecosystem management? In a previous post, I talked about how I couldn’t think of a single instance of ecology being used to make a verifiable prediction of ecosystems. In the same way, frameworks may be useful for ecologists to understand how ecosystems work but ultimately the framework itself is self-serving. In my opinion, it would be great to hear more stories about how ecological findings actually change the way we manage or predict ecosystem trajectories. A great example is how studies have counteracted the notion of universal tree planting by documenting belowground carbon storage in ecosystems previously thought to be unproductive, such as grasslands.

- I suspect the number of citations generated by publications outside journals and mainstream academic sources remains fairly low, but I could be wrong on this. Citations by industry reports have the potential to be really impactful and applicable to the projects they document, but this is virtually impossible to compile systematically. At the same time, industries are notorious for ignoring/failing to consult academic consensus. One instance that pops up in my recent memory is how the Verified Carbon Standards (VCS) by Verra still doesn’t incorporate carbon losses from soils as part of their calculations to determine carbon gain/loss in deforested tropical forests (VM0048), despite the clear evidence that logging enhances soil carbon loss.

- At the end of the day, citations are just what they are – a single metric of impact. In theory, even a single uncited paper could spark a Eureka moment in a budding student, leading to a revolutionary finding in the future. No metric will be able to capture this effect.

What do you make out of these trends? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a comment