To believers who stumble upon this post, what tenets of the Christian faith will you classify as “truth”? I would venture to guess a common answer would be something along the lines of “Everything in the Bible”, or “Whatever the church teaches” etc.

When I first came across Dr. Fredriksen’s book in the library with a spicy title such as “Ancient Christianities” in the library, it immediately caught my eye. How strange is it to see the word “Christianity” to be used in a plural form (isn’t there only one Christianity?). A few minutes later, the book was sitting in my backpack on its way home.

No, the plural in the title isn’t a typo. Dr. Fredriksen’s book was published October last year, but it contains a wealth of information on the early state of the church(es?) and just how diverse Christianity was – far beyond what the book of Acts, or Paul’s letters depict. I spent over the past month pouring through her book, fascinated by the wealth of information she portrays, and the kinds of questions historians ask regarding the ancient development of the most widespread religion in modern times. I thought it would be interesting to share my thoughts on the book, as well as its theological implications on believers today.

Firstly, the book is hard. Fredriksen’s writing style is incredibly dense in its language and vocabulary, even for a native English speaker such as myself. There is a lot of room to reduce the complexity of the vocabulary used to make the text more accessible, especially to those whose first language is not English. While the content is certainly engaging, judging based on linguistic style alone, I prefer to read the trade books by Dr. Bart Ehrman. This is by no means throwing shade on her writing, but I would rather have a book that did not fry my brains to parse through every dozen pages or so. Maybe I need to go back to Grade 12 English.

My next few points will cover the key elements of the book that I find most eye-catching and interesting from the perspective of a believer. Some of these will blow the minds of the average believer (it blew my mind when I read it).

Was Jesus God? How did Jesus relate to God?

Among all the Christian tenets and truth claims that we take for granted today, only one appeared to be consistently agreed on by all believers – that Christ died and resurrected.

That was it. The early Christians didn’t even agree immediately that Jesus was God, at least in the way we think of God as a supreme ultimate deity today.

In modern times, we are used to thinking that divinity was a binary status – either you are God, or you are not. Jesus is divine, thus Jesus is God – plain and simple. Yet, looking at what ancient believers believed within a Greco-Roman world, the divine realm was filled with all sorts of beings – think angels, nephilims, lower demigods, the Supreme One (often referred to as God the Father) etc. (this view was persistent even in the Old Testament!). For a long time, Jesus did not sit on top on the divine hierarchy wielding authority equal to the Father (nevermind being the same essence as the Father, as what modern Trinitarianism claims), but remained subordinate to the Supreme One. Bringing this perspective into mind sheds a whole new kind of light on bible verses, such as John 14:28.

“You heard me say to you, ‘I am going away, and I am coming to you.’ If you loved me, you would rejoice that I am going to the Father, because the Father is greater than I. (John 14:28 NRSVUE)

As an example, early Christian authors such as Marcion (AD 85-160) and Valentinius (AD 100-180) understood the divine hierarchy in their own way, and Jesus’s position within that hierarchy. Marcion believed the Jewish God of the OT was different, and subordinate to the God of the NT. Inferring from Jewish Scriptures, the Jewish God was legalistic and indulged in blood sacrifices; the God of Christ was all-loving and unchanging. These two portrayals of “gods” cannot be reconciled, thus Marcion postulated that there were two gods at work, the former subject to the latter and Christ’s mission was to unveil the former and to reconcile people to the latter. Valentinus postulated that Creation comprised of the spiritual realm and the material realm, and the gospel given by Christ revealed knowledge that allowed people to know God once again, and free themselves from the material realm (a precursor to gnosticism). In his worldview (deduced from a letter by Valentinius’s disciple Ptolemy), there was God the Father who reigned supreme, followed by “Christ, then the demiurgical god associated with the God of the Jews; and lastly the devil” (quoted from Fredriksen’s book). This pissed off later writers such as St. Justin Martyr, who claimed such interpretations as heresy).

Later in the book, Fredriksen elaborates on the idea of what it meant to be “divine”, especially in a culture where kings and emperors claimed divine status as they ruled. This was not thought to be something odd back then, since the divine realm could be filled by multiple entities (for example, Hercules was considered divine in some sense). As the years went by, Christians started ranking Jesus higher up the divine ladder – first as the “adopted” Son of God (when Jesus was baptized), then a “divine” being from birth (via the virgin birth); even more so later when Jesus is described as the Logos – a divine figure that was always there from the start alongside God the Father. For a more precise, yet easy-to-read treatment on this development of Jesus’s divinity status, I recommend reading Dr. Bart Ehrman’s book “How Jesus became God”.

“And just as he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove upon him. And a voice came from the heavens, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.” (Mark 1:10-11 NRSVUE)

Mary said to the angel, “How can this be, since I am a virgin?” The angel said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God. (Luke 1:34-35 NRSVUE)

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. (John 1:1-2 NRSVUE)

An adjacent question that troubled early believers was: “Was Jesus fully man, fully divine, or something else?”. We know from early theological writings that while most accepted that Jesus was crucified and resurrected (either through oral tradition or written letters), interpreting this major event to deduce Jesus’s divine/human status was challenging and brought friction among believers. Some of these theologies included:

- Docetism: Christ only “appeared” to have suffered on the cross; He had no physical flesh and could not suffer, since He was so divine He could not suffer. He only appeared to do so to achieve his gnostic mission on Earth.

- Adoptionism: Christ was initially fully man but was later adopted to be divine by the Father (exactly when was also a matter of debate).

- Modalism: The Supreme God was one single entity but served different functions in different modes – as the grand ruler (Father), the suffering redeemer (Son) and the Holy Ghost (Spirit). However, this was deemed heretical as it could be inferred that the Father suffered on the cross.

- Arianism: Proposed by a priest named Arius (AD 256-336), Jesus was an entity that was created by the Father before the beginning of time, thus He had a divinity that was inferior to the Father (or in Fredriksen’s words, the Son was contingent on the Father). Why this became heretical is an easy guess…

Who was deciding what “orthodoxy” entails?

A common theme popped up in every chapter and discourse throughout the book – who were the ones initiating the arguments, throwing shade and leading the charge towards establishing orthodoxy?

Valentinus. Marcion, Oriegen. Augustine. Constantine. Justin. Clement. Philo. These were the names and titles that popped up time and time again. What did they all have in common? They were all either philosophers, bishops or rulers – highly educated people with great concentrations of authority and power. Almost nowhere you hear the laymen’s opinion.

To the average historian, this isn’t a particularly big surprise since education was virtually inaccessible to all but the highest echelons of society. Only those with sufficient wealth and authority could engage in such discourse without the need to tend to their farms or do whatever the layman needed to do to eat.

To me, the fact that centuries of discourse was needed to hammer out the core tenets of modern-day Christianity makes it abundantly clear that while Scripture important to early Christians for many reasons, clarity isn’t one of Scripture’s strong suits. Furthermore, this would mean that discerning the Word of God was accessible only to an extremely small proportion of the population who was wealthy, educated, powerful and free enough to do so. The rest likely simply followed suit; their version of “truth” handed to them in neat packages by their local bishops. In fact, the origin of the word “orthodoxy” means “correct belief” (orthos = correct; doxa = opinion), but this belief did not arrive quickly nor stayed static nor was achieved through a diverse group of participants engaging in civil discourse.

For God is not a God of disorder but of peace—as in all the congregations of the Lord’s people. (1 Corinthians 14:33 NRSVUE)

What did early believers do with this newfound faith?

Modern-day believers will be abhorred by this.

Dr. Fredriksen discussed in detail how ancient societies perceived themselves with respect to the divine realm of gods. Basically, the contract between society and gods could be summarised into two points: how did the gods intervene in their daily lives, and how not to piss them off. Within these two points, all sorts of activities prevailed – many that will send modern believers twisting their faces in disdain.

Magic and oracles? Check. Amulets? Check. Prostitution? Check. Celebrating pagan and Roman festivities? Check.

Not all deeds were as deplorable, or had such a hedonistic flavor. Some Christians arrived at a different conclusion looking at Scripture and devoted their lives to ascetism – a way of life that emphasizes giving up on mortal possessions and pleasures in life to live minimally in anticipation of God’s return (probably motivated by Matt 19:21). Some groups cohabited (men and women together!) but refrained from sex (such a contrast compared to modern takes). Others lived out their lives like many of us today – marrying, having sex, conceiving offspring. Even the idea whether sex was desirable or not became a debate – so much for Gen 1:28!

God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth… (Gen 1:28a)

We might never know for sure whether the majority of laymen Christians actively participated in these activities that we deem as heretical today – after all, no one was taking a census on who’s Christian and who wasn’t. To be fair, bishops did denounce and discourage these activities among their congregations. Nevertheless, it is still interesting (and probably a huge shock factor) to think that God’s holy people aren’t as distinguishable in their lifestyles as one would expect.

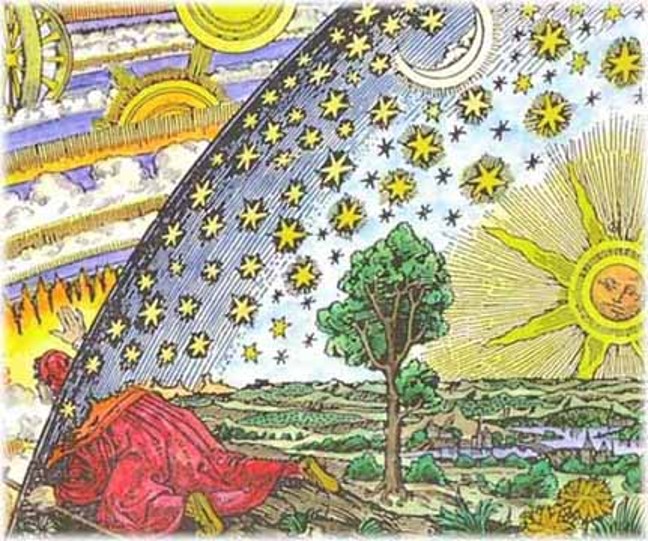

Why would early Christian act that way though? Shouldn’t they know better from Scripture? For one, there was no such thing as an official biblical canon that people could refer to on a regular basis; at least for the first few centuries of the faith. Secondly, in the words of Fredriksen, “God and demons, intellectuals and enthusiasts, sacraments and magic, interurban and intraurban politics, new disciplinary behaviours and social formations: all went into the mix.”. The priority of the layman was not to obtain a correct theological outlook; it was to adhere to tradition and culture – whatever those were in their lifetimes. It was to please the deities, and to look forward to a good afterlife. Proper Christian lifestyle as we understand it today mattered more to the elite clergy and less so to the common man – and it showed prominently in how they lived. In fact, it could be argued that these people consulted mediums, astrologers and diviners precisely because they strongly believed in God and sought ways to recruit divine protection for themselves and to make sense of His presence in their everyday lives.

Astrologers, diviners, makers of amulets, healers, celebrants at martyrs’ graves and at urban spectacles: the highbrow rebuffed all these Christians as “pagans”. They answered back, “I am baptized, just as you are.” (In Chapter 7: Pagan and Christian)

Part II and closing thoughts

As this post is getting too long. I’ll continue with this section in a later post, along with my thoughts on what this means to the lives and beliefs of believers today. Stay tuned!

Leave a comment