What is biodiversity?

In today’s environmental crisis, biodiversity is a buzzword that everyone has a rough sense of what it entails, but not many can come up with a holistic definition for it. Ask any layman on the street and the most likely answer will fall along the lines of “the number of species in a location”, or “species composition”. Look up any industry framework on biodiversity such as the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) and the focus will remain on species abundances.

While it is true that a component of biodiversity is indeed species abundance, such a narrow view of biodiversity has declined in popularity in favor of other ways to make sense of ecological communities.

In this post, I wanted to highlight some recent developments in how ecologists view biodiversity and how these new perspectives align (or remain excluded) from the mainstream conversations on biodiversity and its utility today.

An old field: Biodiversity-ecosystem functioning studies

Operationally, biodiversity is often mentioned in public discourse in terms of its utility. Think about it: why does society collectively care so much about biodiversity decline in modern times? While any one person may desire to protect biodiversity for a number of reasons, it is safe to say that the current urgency regarding biodiversity decline is largely because losing species equates to losing the utility derived from them.

Biodiversity is fundamental to human well-being, a healthy planet, and economic prosperity for all people, including for living well in balance and in harmony with Mother Earth. We depend on it for food, medicine, energy, clean air and water, security from natural disasters as well as recreation and cultural inspiration, and it supports all systems of life on Earth. – Kumming-Montreal GBF, Section A1

Exactly what is it about biodiversity that promotes ecosystem functioning and generates the services we care about, however? While there is a clear utilitarian desire to protect biodiversity, the link between species and ecosystem functioning and services isn’t as clearcut as one might think. In fact, this is one of the hardest questions to answer in ecology, and has been the subject of ongoing research for over half a century.

Enter the realm of biodiversity-ecosystem functioning (BEF) studies.

Ever since the late 20th century, ecologists have experimented with carefully-crafted experimental systems in order to test numerous hypotheses and mechanisms on how biodiversity influences ecosystem functioning. For example, one of the most famous BEF monitoring plots was set up at Cedar Creek, Minnesota, where Dr. David Tilman and colleagues tested the productivity and resilience different plots containing independent assortments of plant species. Broadly, the authors reported positive findings: plots with more species do express increases in aboveground and total biomass, increased drought resistance and greater ecosystem stability.

That’s the end of the debate, right? More species == better ecosystem!

Not so fast. For one, the results of the BEF study have been interpreted in diverse (pardon the pun), sometimes divisive ways. For example, does the increase in productivity due to more of any species in any plots? Or is it the presence of one or more superstar species that’s artificially jacking up the productivity numbers? How generalizable is this result – can the same productivity gains be realized if one repeats the experiment using different species combinations? Or perhaps that is the whole point of keeping as many species as possible, so that we can have a greater chance of capturing one of these highly productive species.

There is so much one can ask from these findings. It’s a fascinating area of research, but like any empirical study, it can only tell us so much. We need a better way to represent biodiversity in order to connect it to function.

From species to function

Around the time when BEF studies took off, other ecologists pondered on the same question of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, though from a slightly different place. In practice, nature doesn’t recognize what a “species” is. A species is simply a name we give a unit of organisms that cannot reproduce with another such unit. And even this definition isn’t foolproof (e.g. ligers from tigers and lions, or hybridization in plants). In short, by focusing too much on species, we have gatekept our minds into thinking the number of units is what matters for ecosystem functioning, instead of the more pertinent question: what are they doing?

How does one go about representing and measuring what species “do”? Enter the world of functional ecology*.

*This is a core area of research that I worked on for my doctorate, though my perspectives in the next few paragraphs will be largely skewed from what I know from studying plant functional ecology.

In the words of the late pioneer ecologist Charles Elton “it is natural to ask: what are they doing?”. Functional ecology answers how species interact in an ecosystem, with respect to the abiotic environment, within conspecific individuals and with other members of the community. Very broadly, the field proxies the performance and interactions of a species or individual by measuring functional traits – morphological, physiological or phenological features of an organism that impacts its own fitness. This gives rise to new ways to represent biodiversity – not just in terms of species but in terms of species’ functional traits.

Subsequently, ecologists are now able to make sense of biodiversity in more concrete, mechanistic ways on how the presence of species can drive key ecosystem processes such as plant productivity, ecosystem stability etc. We can quantitatively analyze how species respond to abiotic factors, using all the powers granted to us by statistics as opposed to qualitative descriptions. We can link these traits to other aspects of community ecology, such as resource utilization, niche segregation and competition. In my view, this is one of the most important paradigm shifts in ecology – representing species diversity in terms of functional traits that drive ecosystem processes.

Like any novel methods in science, there remains much work to be done within functional ecology to make it truly powerful for predicting ecosystem processes. For example, figuring out which traits are truly “functional” demands strong empirical evidence; something that remains an ongoing exercise till today. Also, traits vary at multiple scales from within species, across species, across communities and across lineages, making it difficult to disentangle the different levels of trait variation on which natural selection acts. Nonetheless, this paradigm shift is a great leap forward beyond focusing on species and potentially holds the key to unlocking why biodiversity is critical for ecosystem functioning.

Beyond species diversity in community ecology

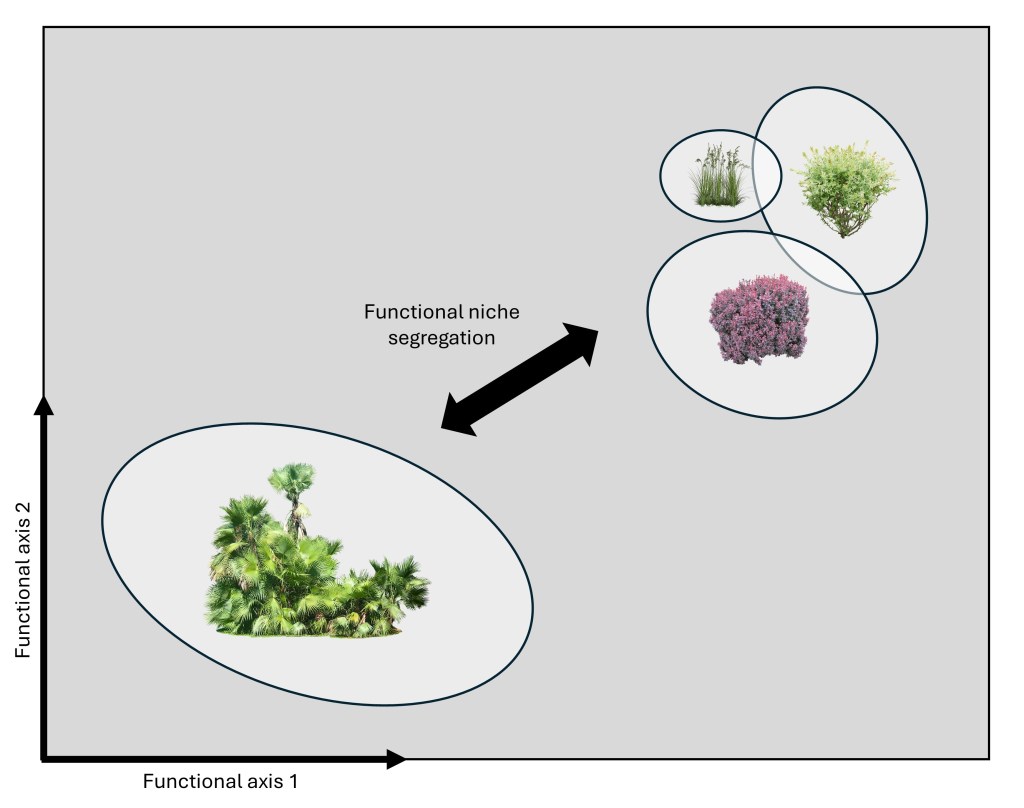

At higher organization levels, the diversity of organisms within ecosystems can now be represented in ways that go beyond the number and ratio of species. For example, the entire space of species’ traits can be represented geometrically as a multidimensional trait space. Functionally similar subsets of species are clustered within a segment of this space, representing a shared “niche” of sorts. Other functionally distinct individuals occupy other parts of the space, effectively reducing niche overlap and facilitating coexistence based on distinct functional niches.

The examples I have shown are largely derived from my knowledge on studying plant functional ecology. Yet, the same ideas can be applied to any taxa (e.g. animals or microbes), and even to other aspects of biological diversity. Some of these emerging ideas include:

- Genetic diversity – individuals with distinct genotypes are expected to have distinct phenotypes and/or physiologies, which may be essential to adapt to variations in abiotic conditions

- Phylogenetic diversity – species that are phylogenetically distant from each other are expected to have underwent distinct evolutionary trajectories, which may indicate past exposure to different abiotic conditions that selects for unique physiological features

Stuck in our old ways?

The main takeaway from laying out these concepts is not in the details (unless you are a fellow colleague in this field!). Rather, I hope that through this post I have sufficiently explained how biological diversity occurs at so many levels, and the powerful options we have at our disposal today to measure said diversity to better advance ecological goals.

While any mainstream ecologist should be familiar with some of these concepts, most layman are still entrenched in our old ways of seeing biodiversity solely through species abundances. I see virtually no mention of species’ functions within the mainstream conversation about biodiversity in the media, or among industry stakeholders. And I think that’s a shame because we end up with a myopic view of biodiversity that does not do justice to the vast majority of species in the wild that may be functionally important yet neglected for other reasons.

More importantly, viewing biodiversity in terms of species count reduces biodiversity to a mere statistic void of meaning, hiding what makes biodiversity important for human and ecological well-being in the first place. As Goodhart’s law goes: “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure” – the same is true when stakeholders make species abundances a target for biodiversity conservation outcomes. Just like the greenwashing efforts of the carbon credits market, I wouldn’t be too surprised if biodiversity credits market start their own line of greenwashing in the near future, either by fudging baselines or overexaggerating species recovery numbers at the expense of functionally important species.

Perhaps the world will slowly warm up to the ideas brought up by functional ecologists to rethink the way we evaluate the ecological importance of biodiversity. Unlike carbon, the damage to biodiversity will be 100% irreversible once done, for there is no way to bring back a species once it’s gone forever. Let’s hope we quickly identify and protect the ones that functionally matter the most to us and to ecosystems, before it is too late.

Leave a comment