My first ever post on this blog covered the extent of academic fraud. Ten months later, the problem only seemed to be getting worse with the advent of generative AI and papers flooding the academic scene.

But who are the guiltiest actors of these shenanigans in science? I came across this news article covering how China has overtaken the US to become the new leader of the pack of scientific output – a title that the US has held for as long as anyone can remember. While it is true that Chinese scientists have been putting out some great work recently, it is from my experience that among the gems lies a whole bunch of coal. And at least in my field of research, a whole mountain of coal. But was my bias simply due to the anti-Chinese portrayals by the western media rubbing onto me? Or is there some truth in this bias?

Luckily (or unluckily), there exists a list of retractions by Retraction Watch that regularly updates the withdrawal and retraction of published scientific literature. With their list of retraction records, anyone around the world can download the data to see for themselves which countries contribute the most fraudulent scientific literature. Here’s what I found from some quick, surface-level analysis.

Actors of scientific fraud – according to Retraction Watch

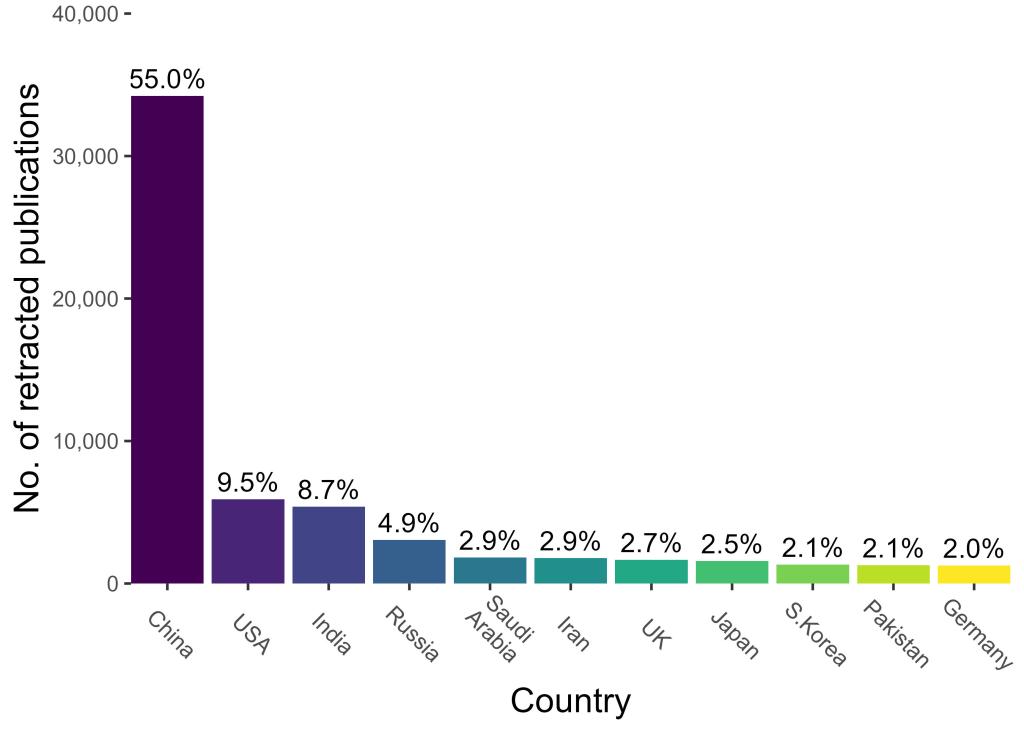

Downloading the raw data from Retraction Watch’s database yielded 67,747 records. After doing some quick data sieving to include only retraction entries, I was left with 62,218 entries. Among these entries, China led the pack with over 34,000 retractions – that’s 55% of all retractions in the dataset! Other countries with notable retraction numbers include the United States (2nd, 5919 publications), India (3rd, 5400 publications), Russia (4th, 3059 publications) and Saudi Arabia (5th, 1833 publications).

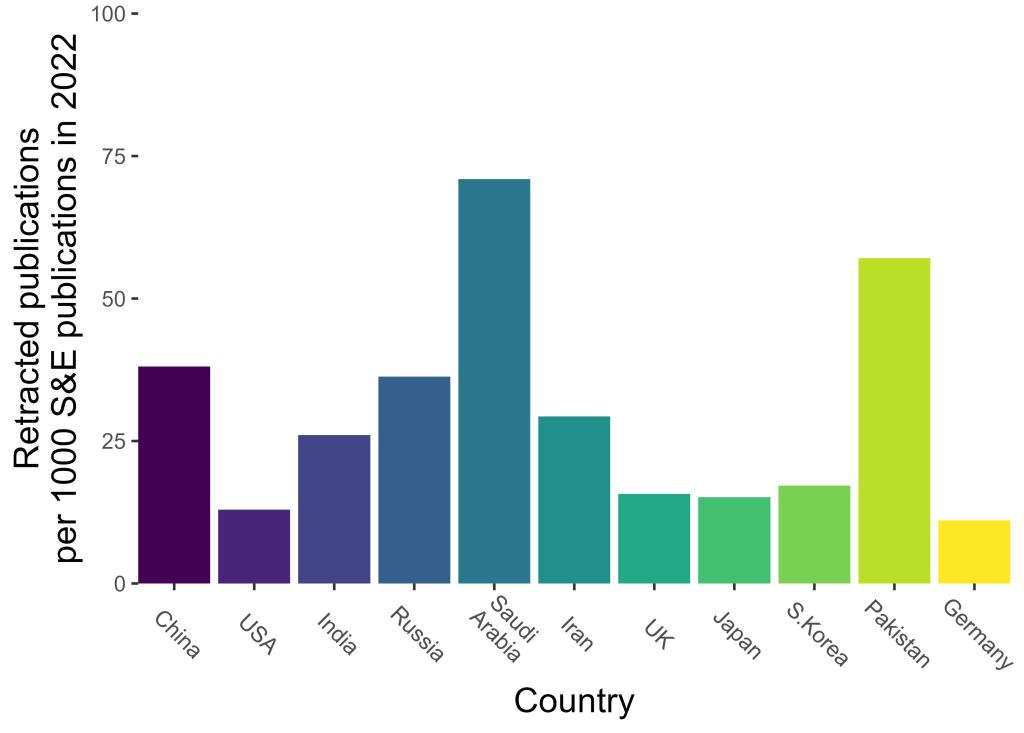

Now, these numbers do not tell the whole story as the number of publications produced by each country is highly variable. To correct for the differences in publication rates by country, I turned to the World Bank group and tallied the number of scientific and technical articles from each country in 2022 (as a proxy for publication rates). The next graph presents the same retraction data but standardized by each country’s publication rates in 2022 (in descending order, starting from the country with the most publications).

What jumps out to me from this second graph is the sheer rates of retractions of several countries. For example, why is Saudi Arabia’s and Pakistan’s retraction rates so much higher than the rest? Even more interesting is the retraction rates of the top three nations with the most scientific publications (China, USA and India). Based on World Bank numbers, China published nearly twice as many S&E articles as the US in 2022, yet they produced ~6 times more retracted publications than the US. Conversely, the US published more than twice as many S&E articles as India in 2022, yet their retraction rates is half of India’s. In contrast, the strong total publication numbers of the US along with their relatively low retraction rate (roughly 13 out of every 1000 articles) allows them to continue reigning as a leader of the world’s scientific output.

The world is slowly turning to China as the next superpower in science. Yet, their track record on retractions appears to be less than stellar at the moment, suggesting there remains systemic issues that incentivize or pressure Chinese institutions to produce subpar, if not outright fraudulent publications (such as terrible academic culture). While this does not diminish the valuable work produced by Chinese researchers in recent years, it does suggest that top-quality, prestigious research remains concentrated in the most elite universities and research institutions in China, and may not extend to other less prestigious or well-equipped research groups nationwide.

Academic misconduct in ecology?

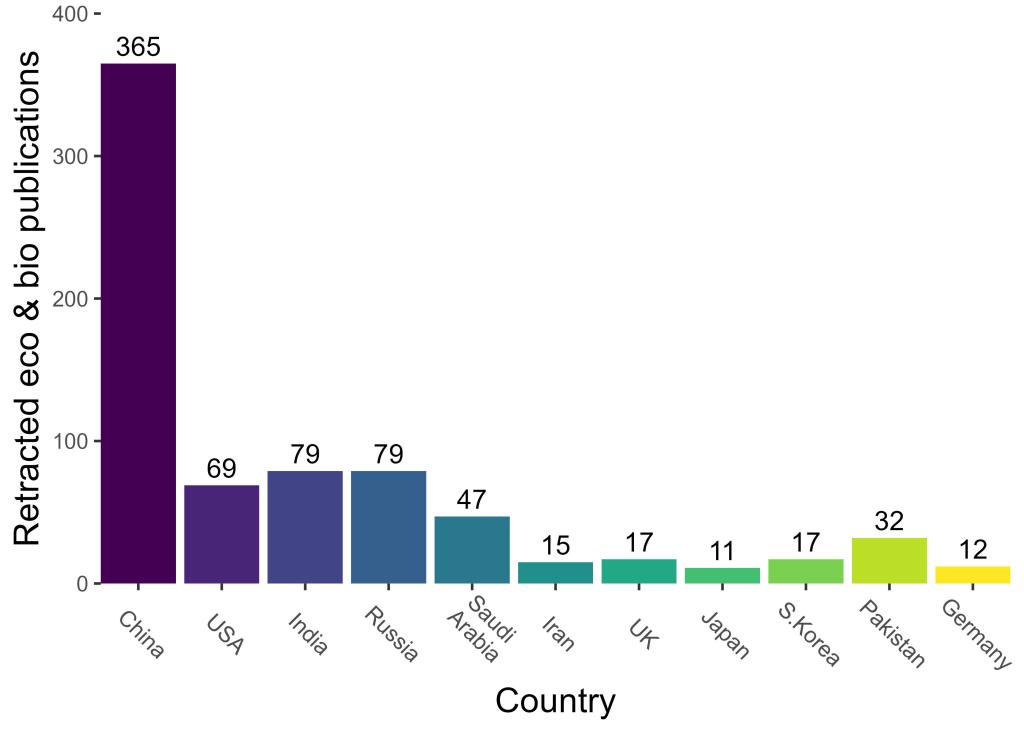

The numbers above were for all scientific fields. What about retractions solely in the field of ecology?

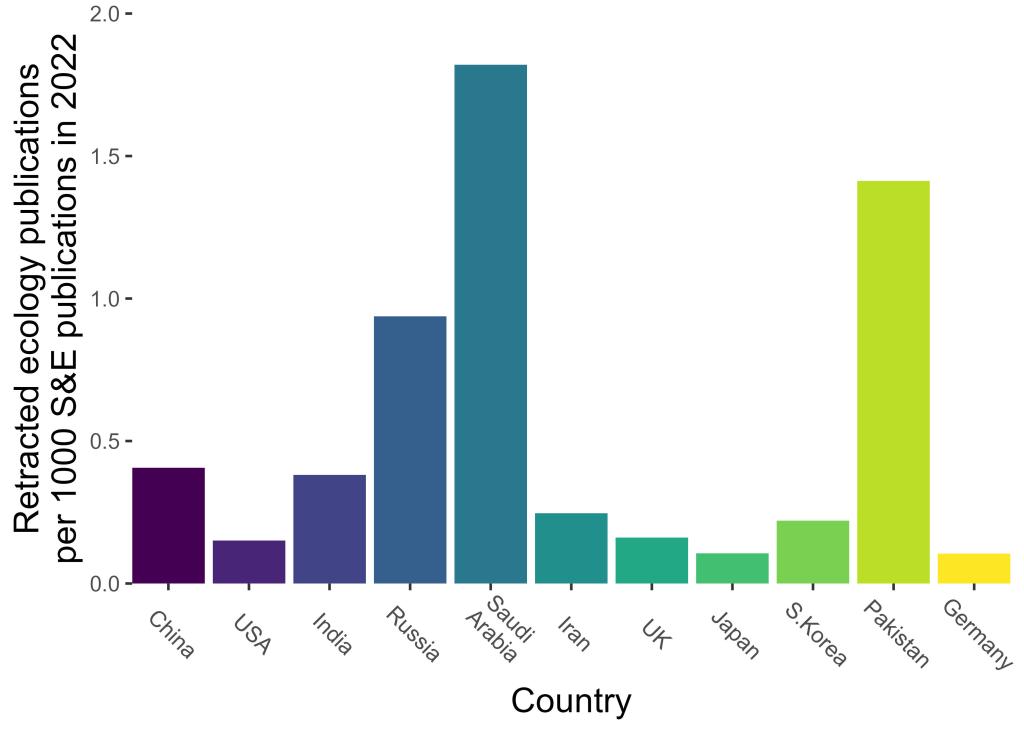

After filtering the data further to include only publications in the fields of ecology or biological life sciences, I was left with 755 studies. China continues to lead the pack, producing nearly half of these ecology/biology publications retracted. Otherwise, the same pattern emerges – disproportionate rates of retraction in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and concerning numbers from Russia, China and India; all of which have retraction rates of ecology publications at least double that of the world’s previous leading superpower in the quantity of scientific output – the US.

These countries are sus! Now what?

While these numbers give us a glimpse of the state of academic publishing across nations, I don’t want to insinuate scientists should be chucking all studies from places such as China, Russia and Saudi Arabia solely due to their higher-than-average retraction rates. Every work should be scrutinized critically and fairly, regardless of nationality!

At the same time, is it truly possible for scientists to scrutinize fairly? I would like to believe that as a peer reviewer, I give each manuscript a truly fair chance by refraining from being overly skeptical/cynical and harsh, and providing constructive criticism. Yet, I am only human, and I’m sure my implicit bias creeps in occasionally (and I’m sure that’s true for anyone that isn’t an AI). Whenever I see a paper from India or China, my alert meter turns on, and I immediately begin paying just a bit more attention. Perhaps this could be due to negative past experiences as a reviewer (I did encounter borderline fraudulent statistics from past studies from China), but it doesn’t excuse my differential cynicism towards studies from those regions. I don’t want to have this differential treatment in my work. Yet, I have no doubt there are colleagues out there that also share my disdain from studies produced from specific parts of the world (in fact, it has been demonstrated here). And honestly, with the rise of paper mills, who can blame them?

I don’t think the academic community has a good solution to this implicit discrimination issue with the systems in place right now. Double-blind peer review may be one way to get reviewers to temporarily withhold their judgement (and thereby, implicit bias). However, in a field like ecology where the site of study must be identified (and it often carries ecological significance because of how biodiversity is distributed globally), it is not rocket science to figure out the source country of the study. Once that is figured out, implicit bias can creep in, even to the best of us.

I don’t like to admit I have a bias in reviewing my peers’ work. And ethically, I know I shouldn’t have such a bias clouding my judgement. Practically, I can only partially circumvent it by exercising best practices whenever I do peer review: 1) give constructive criticism; 2) be gracious when facing terrible English; and 3) try to be consistently thorough in reviewing, such as ensuring citations do report what the authors say they do. Nevertheless, controlling one’s level of skepticism isn’t easy nor quantifiable as long as one remains human. Nor do I know of a system that can allow people to maintain a healthy, consistent level of skepticism to reduce noise and biases entering the publication process.

Maybe someday, someone will have a solution to this problem. But until then, this can join the list of issues that plague the academic publishing system (here, here and here).

Leave a comment